There was perhaps a more thorough discussion this time than in previous years about what constitutes the essential role of national book prizes. What are literature prizes supposed to achieve? To what extent is it permissible to politicise them through the choice of winner? In addition to making judgements about a book’s artistic quality and narratorial originality, is it acceptable to use the jury process (longlist, shortlist, choice of winner) to put down ‘markers’? And if so, what would that mean for very good books that on the face of it don’t offer an insight into the contemporary historical situation? These are legitimate questions that are viewed differently by juries from year to year. While in the end one winner has to emerge, the discussions leading to the choice of books for the long and short lists do take place about actual books amongst actual people dedicated to books. The discussions this year have been striking for a whole variety of different reasons.

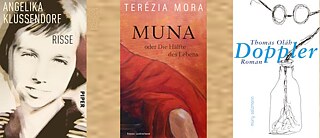

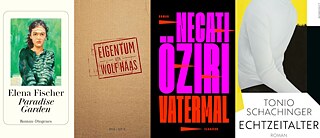

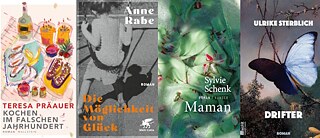

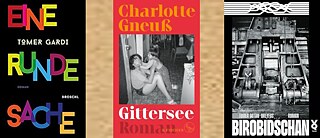

‘Migration literature’ appears to have become less of a trend. Though not to the detriment of the theme of migration as such. The situation is rather more that the perspective has shifted to embrace the actual phenomenon of migration itself and has become more universal in scope - thanks not least to a variety of forms of autofictional writing, which remains a strong presence this year. Novels by Sylvie Schenk, Necati Öziri, Anne Rabe, Wolf Haas und Angelika Klüssendorf (along with Kim de l’Horizon last year) constitute a larger range of explorations of writers’ backgrounds than was the case just a few years ago. Migration figures decisively in all their novels. Migration from France to Germany in the case of Sylvie Schenk’s mother-centred novel Maman. Migration from Turkey to Germany in the case of Öziri’s novel Vatermal (‘Father mark’). Angelika Klüssendorf and Anne Rabe investigate the migration of people within the two Germanies, their migration away from two systems of injustice (German fascism, and GDR socialism) to the post-Wende Federal Republic with its outbursts of xenophobic violence in the 1990s. Some rather more experimental novels also belong in this category, such as Birobidschan (‘Birobidzhan’) by Tomer Dotan-Dreyfus – an impish novel about an autonomous oblast near the border with China that Stalin briefly proposed to set up for eastern Jews.

In this context I was excited and delighted to learn that this year yet another Jewish writer had captured the hearts of the jury of a German literary prize. Tomer Gardi’s novel Eine runde Sache (Droschl Verlag; ‘And nothing ever ends’), winner of the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2022, had enriched contemporary German literature by bringing to it the perspective and idiom of an Israeli Jew living in Germany. Everything was conjoined here, Jewish literary history and Jewish humour, German-Jewish cultural history, linguistic originality in the book’s exhilarating mix of Hebrew, Yiddish and German, breathtaking acuity in its dialogue and settings.

Tensions at the Book Fair, however, were not limited to issues relating to other countries. There had been bitter arguments beforehand concerning the interpretation of German history. In the run-up to the fair, books by Anne Rabe (Die Möglichkeit von Glück; ‘An opportunity for happiness’) and Charlotte Gneuss (Gittersee; ‘Gittersee, Dresden’) had already stirred up controversy as to what constituted an appropriate assessment of the GDR and the Wende period. The rows focused chiefly on what could be regarded as an ‘appropriate’ response on the part of younger writers. The questions posed by older writers from the GDR and Wende periods were these: what can or indeed must be the ‘right’ way for us to remember the GDR and its after-effects as manifested in the extremes of violence that occurred in the post-Wende period (the so-called ‘Baseball Bat years’)? What sorts of family histories did people take with them when they left the GDR? How, and to what end, should entanglements between dissident families and those loyal to the regime be more searchingly investigated? How does all this relate to the overwhelming appeal of a right-wing populist party in the new Federal States. This year a strikingly large number of books dealt with mother-daughter relationships (often with family-history issues lurking in the background. Anne Rabe, Angelika Klüssendorf, Charlotte Gneuß, Necati Öziri and Terézia Mora all seek to settle the hash of mothers who were egocentric or too stressed out to cope, and in some cases sadistic. Elena Fischer in her enchanting coming-of-age novel (Paradise Garden) conjures up a heroic single-mother in a social-housing estate who fights valiantly to maintain a positive attitude to life, while Wolf Haas (Eigentum; ‘Property’) recounts the realities of the life of his deceased mother, who had lived to a great age and had been moulded in her childhood by the poverty and austerity of the pre-WW2 inflationary period.

Finally, I should like to make an observation about literary style, an aspect that we on this year’s jury found both appealing and compelling. Many of the books we selected celebrate a particularly notable form of comedy. Tragic stories are communicated in comic guise and in the process become sparkling examples of the tragicomical. Thus it was that this year’s Book Prize panel was able to side-step any risk of one-dimensional moralising. This applies particularly in respect of the books by Tomer Dotan-Dreyfus, Necati Öziri, Benjamin von Stuckrad-Barre, Teresa Präauer, Ulrike Sterblich, Elena Fischer, Wolf Haas, Tonio Schachinger and Tim Staffel, whose depictions of social misadventures are complemented by a comic commentary. Struckrad-Barre pillories structural sexism in the media industry; Öziri writes about racism as the reason behind the failure to integrate; Dotan-Dreyfus explores Jewish perspectives within the diaspora. The key issue in Präauer is the bourgeois flaunting of social superiority, in Sterblich it is the murky depths of social media, in Fischer classism; in Staffel’s high-octane novel set in Berlin-Kreuzberg we find a whole plethora of these topics. Tonio Schachinger pulled off the clever trick of writing a Bildungsroman about Austria and a traumatic experience of Bildung that echoes Thomas Bernhard but at the same time is analytically super-rigorous and extremely funny. The humour in many of the books selected for consideration not only constitutes the driving force behind their narratives, but is also the expression of an engagingly undogmatic relationship to the world that impressed us in these turbulent times, and infused us with new energy as an antidote to the currently rampant apathy.

Katharina Teutsch (Spokesperson for the 2023 German Book Prize jury)

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Translated by John Reddick

Copyright: © 2024 Litrix.de