Bookworld

Liverwurst or Baklava?

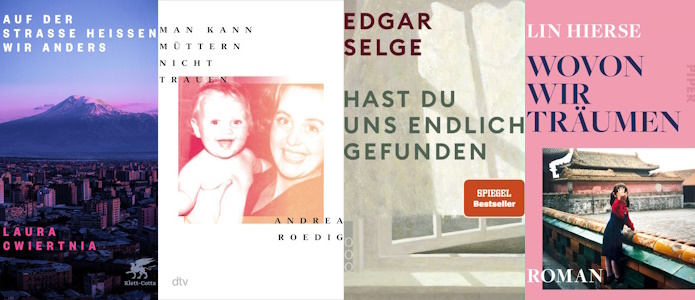

New debuts from Germany. Three women and a man: four authors parse their family backgrounds

by Maike Albath

The German mother — a permanent fixture of the immediate post-war era. Her job was to be there for her husband and children, set the table nicely for coffee and cake in the afternoon, and make sure everybody was getting along. The facade was supposed to look bright and shiny, the injuries just barely covered. When the traumatic experiences of war indeed bubbled to the surface, and the carefully calibrated relationships collapsed as a result, it caused a great deal of uncertainty.

In her gripping autobiographical debut novel Man kann Müttern nicht trauen (cf. You can’t trust mothers), Andrea Roedig focuses on her mother Lilo, who was born in 1938. As a child, the mother had been neglected and was a victim of domestic violence. Later in life, she developed a horrific form of emotional coldness that made it impossible for her to give her daughter and son the love they needed. In fact, her behavior often seemed arbitrary and malicious. Inexplicably, for example, she took Andrea’s stuffed animal away from her, and terrified her relentlessly. Roedig, born 1962 in Düsseldorf, and a seasoned journalist, lays her cards on the table right from the start: she never understood her mother who had turned her back on the family when the author was twelve years old. With a cool head, she seeks to chronicle her childhood, in the hopes of reconstructing the disastrous circumstances of her family background, at least in retrospect. When did things start going wrong?

Lilo’s mother should have been proud of her accomplishments, given how successfully she climbed the social ladder: starting as a salesgirl at a clothing store, she worked her way upward to becoming a highly respected executive, after marrying a well-established butcher in Düsseldorf. Yet, the young woman, who was proud of nothing more than her beauty and narrow waist, felt trapped by her own children: “Disgust, shame, fear and pride. These were the coordinates of Lilo’s system,” remarks Andrea Roedig. On top of it all, there was her irascible father, who was only concerned about his own needs. The one thing he and his wife had in common was their drinking, and how brazenly they let everything go down the drain. Although Andrea Roedig had every legitimate reason to avenge herself in her account, Man kann Müttern nicht trauen is not an angry reckoning, rather it is a sharp-edged investigation. Her one salvation in this West German family hell was her younger brother.

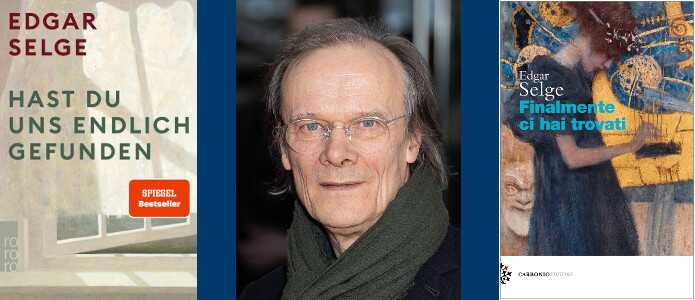

Solidarity between siblings is also crucial for the first-person narrator of Edgar Selge’s autobiographical debut Hast du uns endlich gefunden (cf. Have you finally found us). Selge, born in 1948, and one of Germany’s major actors, dedicates his book (which is not categorized by a specific genre) to his brothers. “My brothers are my gateway to the world,” he writes at one point. The setting is Herford, where the father, a senior public prosecutor, was the director of a prison and lived with his wife and sons on the grounds of the juvenile detention center. In a grandiose mixture of seriousness and gallows humor, Edgar Selge depicts everyday life in the cultivated middle-class household, where the inmates not only built the furniture, but for educational reasons were expected to participate in the concerts at home. A special performance was arranged for the young people in the morning, while in the evening they made music for friends and dignitaries of the small town.

“Now I’m sitting here writing all this down,” observes the first-person narrator about his venture. “Hopefully, I won’t disappear between the sentences. The more precise I become, the stranger I become to myself.” And then the hero and narrator slips back into the events of his childhood that he vividly details, and describes the customs of the “restorative” years in the 1950s. The parents are portrayed as having a strong sense of duty, who sternly watch over their five sons. They can barely cope with the accidental death of their eldest child, who was killed by a hand grenade while playing. Edgar casts his parents strict rules to the wind, and secretly goes to the movies, where he discovers the power of the convincing lies projected on screen.

The older brothers soon confront their father and mother about having been conformists during the Nazi era, and censure them for being anti-Semites. Constantly we are shown the gaping abysses: for example, the father’s secret pleasure in punishing his unruly son, whom he also had sexually molested. Yet despite all the ambivalence, Edgar Selge’s touching book conveys his profound and complex bond with his parents.

The father is also the protagonist of Laura Cwiertnia’s novel Auf der Straße heißen wir anders (cf. We are called something else on the streets). Cwiertnia, born 1987 in Bremen to a German mother and an Armenian father, and deputy department head of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit, processes her own experiences, while weaving them into a fictional plot. Her heroine’s name is Karla, who as a child feels the turmoil of her parents’ generation. Her friends from Bremen, whom she hangs out with at the busstop, think she is Turkish because her father was born in Istanbul. Yet, they also know she is not. But what is she then? “The words turned into a wall between her and the rest of the family,” she once was told, because her father would not speak Turkish with her. The fact that Armenians have a completely different history seems to be something best left unsaid. Nevertheless, the Armenian genocide of 1915 affects her family as well. When her grandmother Maryam dies and leaves her a bracelet, the piece of jewelry turns into a mission: it is up to the granddaughter to travel to Armenia and hand over this pledge to a woman named Lilit, a person nobody in her family knows anything about. Karla convinces her father Avi, who has never set foot in Armenia, to accompany her. The journey brings discoveries for them both.

The author switches narrative perspectives with great virtuosity and repeatedly disrupts the chronology of events: In flashbacks, we are shown the fate of her grandmother Maryam, who traveled to Istanbul and was later recruited as a guest worker for Germany. In Armenia, Karla not only learns more about her family’s background, she also gets to know other facets about Avi. Laura Cwiertnia elucidates the father-daughter relationship with great sensitivity and describes how injustices suffered are encapsulated and passed down through generations.

Similarly to Cwiertnia, Lin Hierse's novel Wovon wir träumen (cf. What we dream of) also begins with a funeral. The funeral rituals for her grandmother, born 1923 in Shoaxing (which during her lifetime had been transformed into the metropolis of Shanghai) is the opening gambit that allows the nameless first-person narrator to deal with questions around belonging. She takes part in the celebrations for her A'bu, her grandmother, and imitates the behavior of her relatives, yet feels as if she is a thief. Lin Hierse, who was born to a Chinese mother in Braunschweig in 1990, and currently works as an editor at the daily newspaper taz, grippingly and vividly depicts her deep inner-conflict. Even though her Chinese is inadequate, her 27-year-old heroine feels a deep connection to the country that her mother had fled for reasons never revealed: “Ma could have had a better life in China, but more than anything, she wanted a different one.”

The young woman explores her mother’s rootlessness, which seems to burden her and which expresses itself through frequent fainting spells. After a sheltered childhood in Lower Saxony, she has long since moved to Berlin, but a complex set of inner rules continues to apply - no wonder she spends a lot of energy constantly doing the opposite of what her mother would have wanted. That said, her mother’s separation anxiety also keeps her in check. She reacts to the excess of affection, which is also a form of control, by falling into states of paralysis. No reaction could be more symbolic. Even her mother’s negative criticism about a new haircut hits her hard. In the end, the mother-daughter duo manage to find a new balance between intimacy and distance.

All four debuts prove one thing: a person’s background offers a plethora of material for writing. And Germany can be just as foreign as China - the need to liberate oneself from family structures and find one’s own place is a universal necessity and task. For this reason, these novels have also been selected for the “New German Voices” series, and have been translated into Italian by young female translators with the support of Litrix.de and the Vera and Volker Doppelfeld Foundation. The four books will be presented to the Italian public for the first time as part of the Guest of Honor event of the German-speaking countries at the Turin International Book Fair from 9-13 May 2024.

Maike Albath is a literary critic and journalist for the radio stations Deutschlandfunk and DeutschlandRadioKultur. She also writes for the newspapers Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Her books “Der Geist von Turin” (2010) and “Rom, Träume “(2013) were published by Berenberg Verlag.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

Books

by Maike Albath

The German mother — a permanent fixture of the immediate post-war era. Her job was to be there for her husband and children, set the table nicely for coffee and cake in the afternoon, and make sure everybody was getting along. The facade was supposed to look bright and shiny, the injuries just barely covered. When the traumatic experiences of war indeed bubbled to the surface, and the carefully calibrated relationships collapsed as a result, it caused a great deal of uncertainty.

In her gripping autobiographical debut novel Man kann Müttern nicht trauen (cf. You can’t trust mothers), Andrea Roedig focuses on her mother Lilo, who was born in 1938. As a child, the mother had been neglected and was a victim of domestic violence. Later in life, she developed a horrific form of emotional coldness that made it impossible for her to give her daughter and son the love they needed. In fact, her behavior often seemed arbitrary and malicious. Inexplicably, for example, she took Andrea’s stuffed animal away from her, and terrified her relentlessly. Roedig, born 1962 in Düsseldorf, and a seasoned journalist, lays her cards on the table right from the start: she never understood her mother who had turned her back on the family when the author was twelve years old. With a cool head, she seeks to chronicle her childhood, in the hopes of reconstructing the disastrous circumstances of her family background, at least in retrospect. When did things start going wrong?

Solidarity between siblings is also crucial for the first-person narrator of Edgar Selge’s autobiographical debut Hast du uns endlich gefunden (cf. Have you finally found us). Selge, born in 1948, and one of Germany’s major actors, dedicates his book (which is not categorized by a specific genre) to his brothers. “My brothers are my gateway to the world,” he writes at one point. The setting is Herford, where the father, a senior public prosecutor, was the director of a prison and lived with his wife and sons on the grounds of the juvenile detention center. In a grandiose mixture of seriousness and gallows humor, Edgar Selge depicts everyday life in the cultivated middle-class household, where the inmates not only built the furniture, but for educational reasons were expected to participate in the concerts at home. A special performance was arranged for the young people in the morning, while in the evening they made music for friends and dignitaries of the small town.

The older brothers soon confront their father and mother about having been conformists during the Nazi era, and censure them for being anti-Semites. Constantly we are shown the gaping abysses: for example, the father’s secret pleasure in punishing his unruly son, whom he also had sexually molested. Yet despite all the ambivalence, Edgar Selge’s touching book conveys his profound and complex bond with his parents.

The father is also the protagonist of Laura Cwiertnia’s novel Auf der Straße heißen wir anders (cf. We are called something else on the streets). Cwiertnia, born 1987 in Bremen to a German mother and an Armenian father, and deputy department head of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit, processes her own experiences, while weaving them into a fictional plot. Her heroine’s name is Karla, who as a child feels the turmoil of her parents’ generation. Her friends from Bremen, whom she hangs out with at the busstop, think she is Turkish because her father was born in Istanbul. Yet, they also know she is not. But what is she then? “The words turned into a wall between her and the rest of the family,” she once was told, because her father would not speak Turkish with her. The fact that Armenians have a completely different history seems to be something best left unsaid. Nevertheless, the Armenian genocide of 1915 affects her family as well. When her grandmother Maryam dies and leaves her a bracelet, the piece of jewelry turns into a mission: it is up to the granddaughter to travel to Armenia and hand over this pledge to a woman named Lilit, a person nobody in her family knows anything about. Karla convinces her father Avi, who has never set foot in Armenia, to accompany her. The journey brings discoveries for them both.

Similarly to Cwiertnia, Lin Hierse's novel Wovon wir träumen (cf. What we dream of) also begins with a funeral. The funeral rituals for her grandmother, born 1923 in Shoaxing (which during her lifetime had been transformed into the metropolis of Shanghai) is the opening gambit that allows the nameless first-person narrator to deal with questions around belonging. She takes part in the celebrations for her A'bu, her grandmother, and imitates the behavior of her relatives, yet feels as if she is a thief. Lin Hierse, who was born to a Chinese mother in Braunschweig in 1990, and currently works as an editor at the daily newspaper taz, grippingly and vividly depicts her deep inner-conflict. Even though her Chinese is inadequate, her 27-year-old heroine feels a deep connection to the country that her mother had fled for reasons never revealed: “Ma could have had a better life in China, but more than anything, she wanted a different one.”

All four debuts prove one thing: a person’s background offers a plethora of material for writing. And Germany can be just as foreign as China - the need to liberate oneself from family structures and find one’s own place is a universal necessity and task. For this reason, these novels have also been selected for the “New German Voices” series, and have been translated into Italian by young female translators with the support of Litrix.de and the Vera and Volker Doppelfeld Foundation. The four books will be presented to the Italian public for the first time as part of the Guest of Honor event of the German-speaking countries at the Turin International Book Fair from 9-13 May 2024.

Maike Albath is a literary critic and journalist for the radio stations Deutschlandfunk and DeutschlandRadioKultur. She also writes for the newspapers Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Her books “Der Geist von Turin” (2010) and “Rom, Träume “(2013) were published by Berenberg Verlag.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

Books

- Laura Cwiertnia, Auf der Straße heißen wir anders. Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart 2022.

- Lin Hierse, Wovon wir träumen. Piper Verlag, München 2022.

- Andrea Roedig, Man kann Müttern nicht trauen. dtv, München 2022.

- Edgar Selge, Hast du uns endlich gefunden. Rowohlt Verlag, Hamburg 2021.