The Literary World

Zerocalcare and Mawil

Zerocalcare and Mawil are comic-book artists in Rome and Berlin respectively. Both are voices of their generation, and in their comics both offer raw yet fond depictions of the realities of a world-ranking city beyond its showcase tourist attractions. What we see here is thus the portrait of two artists who tell the story of everyday life in big cities.

Zerocalcare’s real name is Michele Rech. Born in 1983, he is the son of a French mother and an Italian father. As a child he moved to Rebibbia, a suburb on the north-eastern edge of Rome known chiefly for being the site of Rebibbia Prison.

Zerocalcare has been producing comic books since 2011 - books in which he depicts his own life in a basic tower-block flat in Rebibbia. He himself is the central figure in his comics in the guise of Zero - an ill-humoured youngster in a death’s-head shirt, without self-belief, without a steady job, without the ability to find his way in either life or love, who has steadily evolved into a cult figure, the emblem of a directionless generation. Zerocalcare’s animated Netflix series Strappare lungo i bordi (‘Tear along the dotted line’, 2021) - likewise a depiction of his life in Rebibbia haunted by his fears for the future - is one of the most watched items on the Netflix platform, available in the original version with subtitles in a variety of languages.

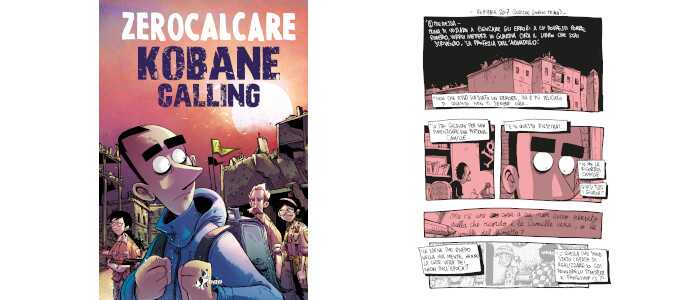

The violent clashes in Genoa in 2001 in connection with the G8 summit made a profound impact on Zerocalcare. In addition to his depictions of everyday life he also writes political comics targeting racism, injustice and police brutality. For his celebrated graphic novel Kobane Calling (Bao Publishing, 2016) he travelled to the Turkish/Syrian border to report on the life of the local population and their resistance to the Islamic State. Like many of his comics, Kobane Calling is an appeal for solidarity. The German version was published by Avant Verlag in 2017.

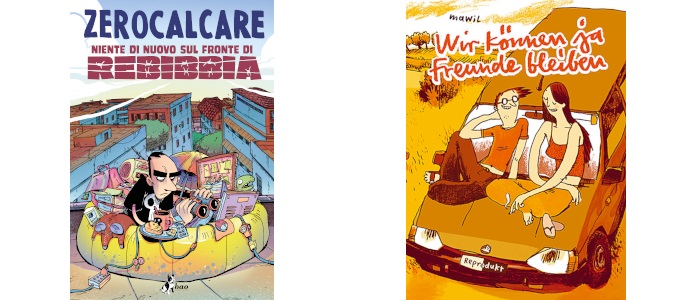

Rebibbia remains nonetheless the real centre of Zerocalcare’s world. In Niente di nuovo sul fronte di Rebibbia (‘Nothing new on the Rebibbia front’), his most recent graphic novel, he describes the lockdown in his suburb on the margins of the city. He depicts Rome as it really is: after all, the rubbish in the streets and the graffiti on the walls are just as much a part of the city as the Colosseum or the Spanish Steps.

Zero is accompanied in his tales by his conscience, personified in an armadillo - a device reminiscent, of course, of Pinocchio and his talking cricket. This is no coincidence, however, given that Zerocalcare is recounting the story of a misdirected, rebellious generation of young people, afflicted at the start of the noughties by unemployment and a total lack of prospects. Even Zerocalcare himself was unable to earn a living through his drawing until 2015; prior to that he had to take on a whole variety of side jobs in order to scrape by.

The comic artist Mawil also portrays the chaos of daily life in a major city - in his case not Rome but Berlin.

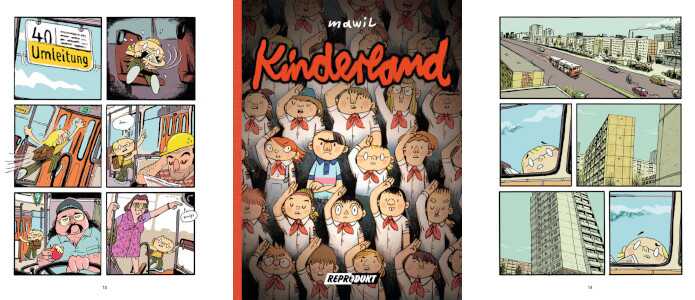

Born in 1976 in East Berlin as Markus Witzel, Mawil has already been writing and drawing coming-of-age stories for some thirty years about lovable losers who never really belong and who never manage to get their girl. His debut book Wir können ja Freunde bleiben (Reprodukt, 2003; ‘We Can Still Be Friends’, Blank Slate, 2003) deals with first-love and with life on a tower-block estate. His breakthrough came with the graphic novel Kinderland (Reprodukt, 2014; ‘Kinderland: A Childhood in East Berlin’, Reprodukt, 2019). This tale of a childhood spent in the German Democratic Republic during its final years, based on Mawil’s own experiences, won the 2014 Max and Moritz Prize, Germany’s premium award for comic books.

Just like Zerocalcare, Mawil is interested in the everyday realities of life in a big city - enjoying a cup of coffee at your gran’s, waiting at a bus stop, kids playing table tennis out in the street. And also like Zerocalcare, Mawil employs the local lingo - in Kinderland it is Berlin’s equivalent of Cockney (e.g. ‘Kannick ooch ma?’ instead of ‘Kann ich auch mal?’). In almost every episode of Strappare lungo i bordi, Secco, Zero’s best friend, asks ‘Annamo a pija’ un gelato?’ - a mantra that is now to be found all over Rome in graffiti on the walls and in conversations in the streets. Properly speaking it should be ‘Andiamo a prendere un gelato?’ (‘How about going for an ice cream?’), but Zerocalcare uses a dialect from Rome’s marginal suburbs (unlike Berlin, Rome has a multiplicity of different dialects: the dialect used in Rebibbia is different from the language used in affluent Parioli).

Mawil’s tone is less frenetic than his Italian colleague’s. The charm of Zerocalcare’s stories derives not least from the fact that he speaks directly to his readers, digresses, embellishes his narrative with pop-cultural references, and constantly seeks the views of his armadillo-shaped conscience. In Kinderland, on the other hand, Mawil relies entirely on the expressive power of his illustrations: the forlornness of a bus stop, a melancholic stare through a bus window, the dismal tower blocks lining the bus route.

But the two artists share a common bond in their love of their cities’ underbellies, their unprepossessing areas, the neighbourhood table-tennis tables, the supermarkets in Rome’s outlying suburbs - all of which they celebrate. They know that everyday life in big cities is not characterised by its fast-paced thrills or its tourist attractions but by the patterns of its bus-seat covers, by evenings spent sitting on a park bench, by the masses of people sharing the same directionless existence.

Lukas Elstermann is a freelance translator and publisher’s reader, inter alia for English-language and Italian comics and graphic novels. He lives and works in Berlin and Rome and writes freelance articles on literature, comics and other aspects of pop culture.

Translated by John Reddick

Copyright: © Litrix.de

Zerocalcare’s real name is Michele Rech. Born in 1983, he is the son of a French mother and an Italian father. As a child he moved to Rebibbia, a suburb on the north-eastern edge of Rome known chiefly for being the site of Rebibbia Prison.

Zerocalcare has been producing comic books since 2011 - books in which he depicts his own life in a basic tower-block flat in Rebibbia. He himself is the central figure in his comics in the guise of Zero - an ill-humoured youngster in a death’s-head shirt, without self-belief, without a steady job, without the ability to find his way in either life or love, who has steadily evolved into a cult figure, the emblem of a directionless generation. Zerocalcare’s animated Netflix series Strappare lungo i bordi (‘Tear along the dotted line’, 2021) - likewise a depiction of his life in Rebibbia haunted by his fears for the future - is one of the most watched items on the Netflix platform, available in the original version with subtitles in a variety of languages.

The violent clashes in Genoa in 2001 in connection with the G8 summit made a profound impact on Zerocalcare. In addition to his depictions of everyday life he also writes political comics targeting racism, injustice and police brutality. For his celebrated graphic novel Kobane Calling (Bao Publishing, 2016) he travelled to the Turkish/Syrian border to report on the life of the local population and their resistance to the Islamic State. Like many of his comics, Kobane Calling is an appeal for solidarity. The German version was published by Avant Verlag in 2017.

Rebibbia remains nonetheless the real centre of Zerocalcare’s world. In Niente di nuovo sul fronte di Rebibbia (‘Nothing new on the Rebibbia front’), his most recent graphic novel, he describes the lockdown in his suburb on the margins of the city. He depicts Rome as it really is: after all, the rubbish in the streets and the graffiti on the walls are just as much a part of the city as the Colosseum or the Spanish Steps.

The comic artist Mawil also portrays the chaos of daily life in a major city - in his case not Rome but Berlin.

Born in 1976 in East Berlin as Markus Witzel, Mawil has already been writing and drawing coming-of-age stories for some thirty years about lovable losers who never really belong and who never manage to get their girl. His debut book Wir können ja Freunde bleiben (Reprodukt, 2003; ‘We Can Still Be Friends’, Blank Slate, 2003) deals with first-love and with life on a tower-block estate. His breakthrough came with the graphic novel Kinderland (Reprodukt, 2014; ‘Kinderland: A Childhood in East Berlin’, Reprodukt, 2019). This tale of a childhood spent in the German Democratic Republic during its final years, based on Mawil’s own experiences, won the 2014 Max and Moritz Prize, Germany’s premium award for comic books.

Just like Zerocalcare, Mawil is interested in the everyday realities of life in a big city - enjoying a cup of coffee at your gran’s, waiting at a bus stop, kids playing table tennis out in the street. And also like Zerocalcare, Mawil employs the local lingo - in Kinderland it is Berlin’s equivalent of Cockney (e.g. ‘Kannick ooch ma?’ instead of ‘Kann ich auch mal?’). In almost every episode of Strappare lungo i bordi, Secco, Zero’s best friend, asks ‘Annamo a pija’ un gelato?’ - a mantra that is now to be found all over Rome in graffiti on the walls and in conversations in the streets. Properly speaking it should be ‘Andiamo a prendere un gelato?’ (‘How about going for an ice cream?’), but Zerocalcare uses a dialect from Rome’s marginal suburbs (unlike Berlin, Rome has a multiplicity of different dialects: the dialect used in Rebibbia is different from the language used in affluent Parioli).

Mawil’s tone is less frenetic than his Italian colleague’s. The charm of Zerocalcare’s stories derives not least from the fact that he speaks directly to his readers, digresses, embellishes his narrative with pop-cultural references, and constantly seeks the views of his armadillo-shaped conscience. In Kinderland, on the other hand, Mawil relies entirely on the expressive power of his illustrations: the forlornness of a bus stop, a melancholic stare through a bus window, the dismal tower blocks lining the bus route.

But the two artists share a common bond in their love of their cities’ underbellies, their unprepossessing areas, the neighbourhood table-tennis tables, the supermarkets in Rome’s outlying suburbs - all of which they celebrate. They know that everyday life in big cities is not characterised by its fast-paced thrills or its tourist attractions but by the patterns of its bus-seat covers, by evenings spent sitting on a park bench, by the masses of people sharing the same directionless existence.

Lukas Elstermann is a freelance translator and publisher’s reader, inter alia for English-language and Italian comics and graphic novels. He lives and works in Berlin and Rome and writes freelance articles on literature, comics and other aspects of pop culture.

Translated by John Reddick

Copyright: © Litrix.de