Bookworld

Reading during the Covid19 years

The digital file comprising the 500 or so titles submitted for the Leipzig Book Fair Prize each year is a sort of microcosm that displays the trends of the day - but also the pseudo-trends: the directions being plugged by publishers, and those that literary critics like to fantasise about. There were also discussions this year on the fundamental question as to what exactly is meant when we ask whether a book is worthy of a prize. On the one hand didacticism and activism have muscled in on the literary world as well as elsewhere, while on the other the politicisation of literature has been countered by those singing the praises of hermetic literature.

These preferences clearly exhibit a wish to convey a picture of society that is more ‘diverse’ than that reflected hitherto in German-language literature. And it may be apt at this point to remember that less than ten years ago we were clamouring for more women to appear on prize lists - an aspiration that morphed into standard practice within a very short period of time, with the result that the authors chosen for consideration were by and large younger and included more women; last year the nominees in the Fiction category were all women except for Christian Kracht! This year, too, the number of women on the shortlist was pleasingly high. We may well now also see an analogous development take place in the form of an expansion of the ‘battleground’ of fiction to include all varieties of migrant themes, languages and traditions. These new perspectives constitute a massive enrichment of German-language literature - especially with respect to the image of German culture that is projected abroad.

Literary critics are happy these days when they see both approaches in tandem with each other; when the all too glib can be rendered palatable by a dash of the hermetic. Thus there were a number of authors this year who won plaudits because their narrative methods were deemed ‘avant-garde’. We might mention Dietmar Dath here, who made it onto the shortlist with his maths-oriented novel Gentzen oder, Betrunken aufräumen (‘Gentzen, or: Sorting things out while drunk’), in which he sought to apply the principles of higher mathematics to the novel’s time frame while simultaneously offering a critique of capitalism. Then there were the thematically sometimes quirky essays of the poet Uljana Wolf, who grappled on an elevated theoretical level with the ethics of translation and was duly rewarded in the Non-fiction category. In the Translation category itself the prize was won by Anne Weber with her rendering of a book by Cécile Wajsbrot that tackled questions concerning the readability and translatability of the world, albeit in a somewhat elitist fashion. Heike Geissler produced a political novel asking whether it is at all possible these days to be political when one is stuck firmly on the treadmill constituted by motherhood, family, and the work routines dictated by the digital, late-capitalist world - a treadmill further exacerbated by the ever more frenetic whirligig of changing values. The novel is interesting in its evocation of a woman’s life in the Leipzig of today, though it comes across as something of a diatribe that leaves little scope for imaginative effects and relies largely on discursiveness.

Things are very different in the case of the winner of the Leipzig prize for fiction. In his novel Eine runde Sache (‘A neatly rounded affair’) Tomer Gardi - an Israeli who has lived in Germany for many years - has turned a captivatingly flawed form of German into true literary diction and thus by dint of sheer playfulness brought to light a whole new dimension of the German language.

There were also some books this year that followed their own particular interests and fitted into neither of the opposing camps of ‘activism’ and ‘aesthetic autonomy’. One such was Ein von Schatten begrenzter Raum (‘A room bounded by shadows’) by Emine Sevgi Özdamar, a book of poeticised reminiscences set variously in Istanbul, Berlin and Paris that veer into the surreal. From her first beginnings Özdamar was categorised as an exponent of migration literature, and as the doyenne of German-Turkish literature she lives up to her allotted role with real virtuosity. An additional aspect here is that Paris figures in a major and thought-provoking way as the central focus of intellectual yearnings in the 1980s.

One author I myself am especially fond of unfortunately didn’t make it onto the shortlist. With her book Die Auflösung des Hauses Decker (‘Clearing out the Decker family home’) Angelika Meier produced a novel fizzing with shrewdness and wit on the culture of the Federal Republic as it used to be. A fragile artist travels to the Ruhr to clear up the genteel villa of her dead father, a former professor, and as a result finds herself confronted with all manner of ghosts from the 1968 era. A touch of Kafka, a dash of Beckett, a sprinkling of the jargon used by the radical-left ‘K-groups’ of the period, and a great deal of Angelika Meier are all to be found in this book.

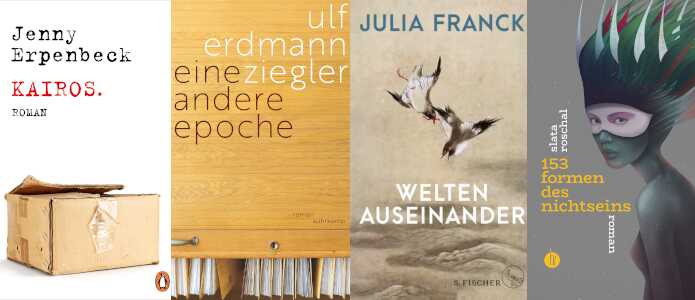

Eine andere Epoche (‘A different era’) by Ulf Erdmann Ziegler is another novel about the Federal Republic, focusing on the political personalities that characterised the early days of the country after Berlin became its capital. The scandal involving the former Federal President Christian Wulff and his wife Bettina is covered here, as are the infamous National Socialist Union murders and the case of the parliamentarian Sebastian Edathy, who stood accused of child pornography. We are shown the mindset of an era that these days seems curiously remote.

In conclusion I should like to recommend the book 153 Formen des Nichtseins (‘153 forms of non-being’). This ingenious and innovative debut novel by Slata Roschal, born 1992 in St. Petersburg, stands out amongst the various books dealing with migrant experiences in Germany. It presents one hundred and fifty three highly diverse evocations of the experience of alienation, entirely free of activist axe-grinding. A small and perfectly formed novel made up of discrete fragments by an author well worth watching.

Copyright: © Litrix.de